Writing

-

The Truth Takes Care of Us

The very indication of what it means to live a contemplative life is “to have faith that our own heart in its most childlike hour did not deceive us.”

-

Recent Publications: Blessings & Reflections

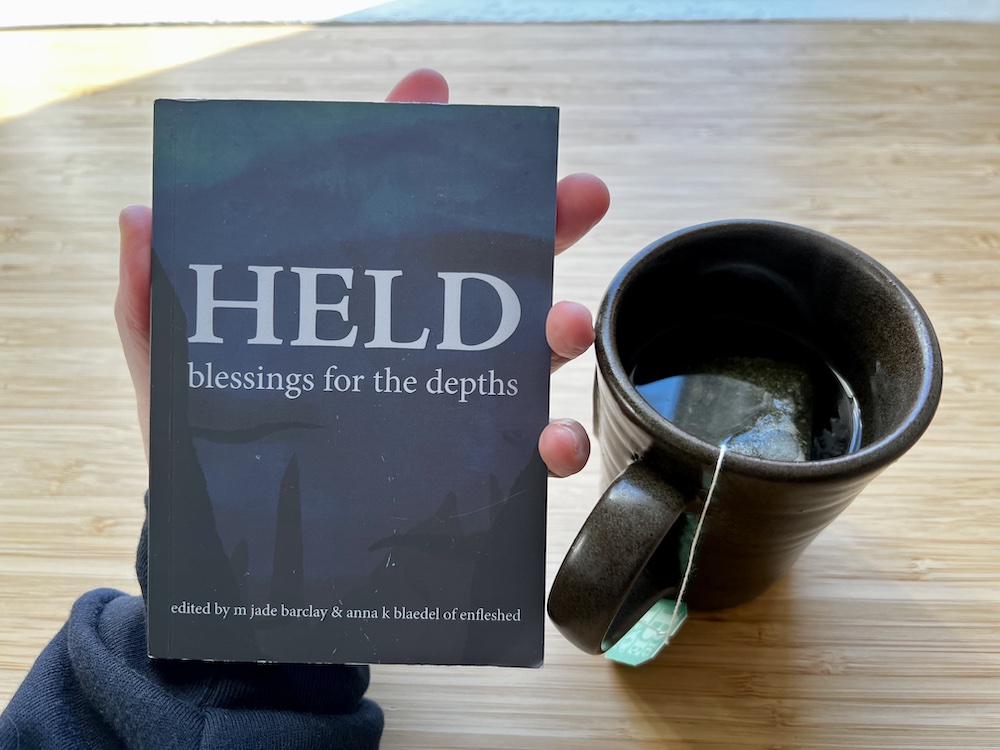

This beautiful compilation of blessings from enflshed was a powerful project to be a part of. You can order this incredible book of blessings, “HELD: blessings for the depths” here. (Note: The first run of the book sold out and this is a pre-order for the second run). You can read the blessing I contributed…