pilgrim

-

The Way of Love; The Way of the Outlaw

The one whose vocation is love lives in a narrative that is controlled by reality.

-

The Tireless Pursuit of Peace

Looking up, I knew this was a moment to behold. Across the living room from me sat Jim Forest, laughing among friends while in Toronto for the first annual Voices For Peace conference. The 76-year-old peace-activist, author, storyteller, and lover of humanity was frozen in a moment of pure joy. I grabbed my camera to…

-

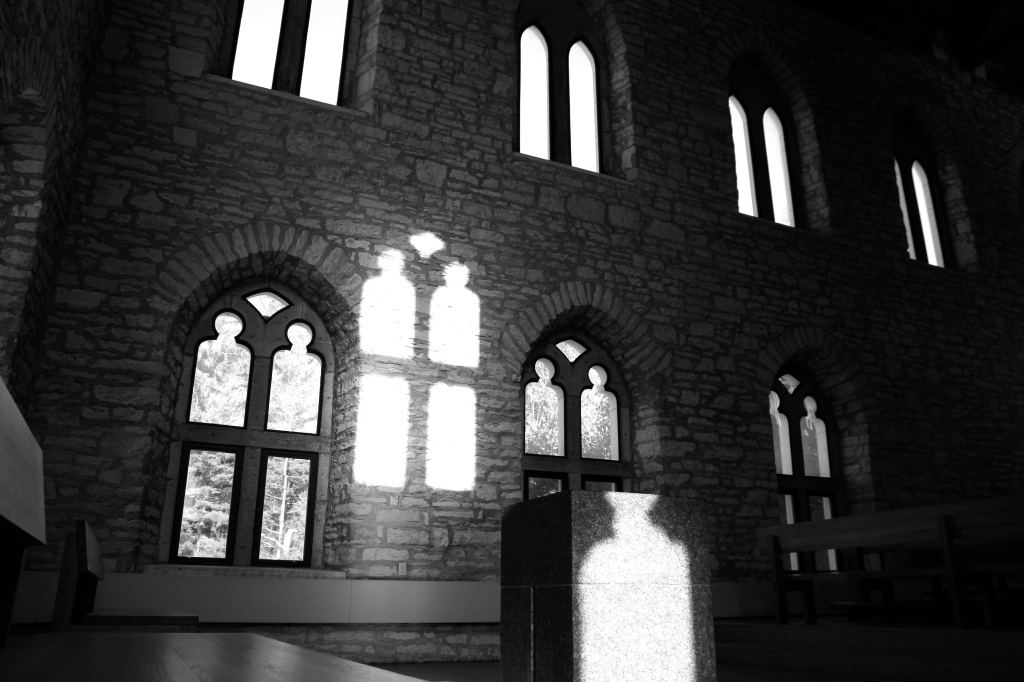

The Uncertainty of Silence

(This will be among the many essays featured in the forthcoming book Notes on Silence that I’m co-authoring with Patrick Shen which can be purchased here.) “…I want to be with those who know secret things or else alone…” Rainer Maria Rilke I was around 8 years old when I began to have reoccurring dreams about…

-

Creating From The Wound

I live in Los Angeles, the epicenter of self-defining artists. And, like most people in this city, I consider myself an artist. However, unlike most people living in Los Angeles — I believe we’re all artists in some form or another. I’m in constant awe of the way people create, perform, produce, and refine their…

-

“Cassidy Hall found silence in an Iowa monastery and brought her discoveries to a new documentary” Des Moines Register

“A cricket chirped in the monastery’s library. That and the swish of a turned page, Thomas Merton’s “New Seeds of Contemplation,” was about it for sound. Cassidy Hall stopped on page 81. Merton did not write on the absence of sound on that page but the abyss of solitude in the soul: “You do not…